Tule Lake National Monument,

California

427th National Park Visited

June 13, 2024

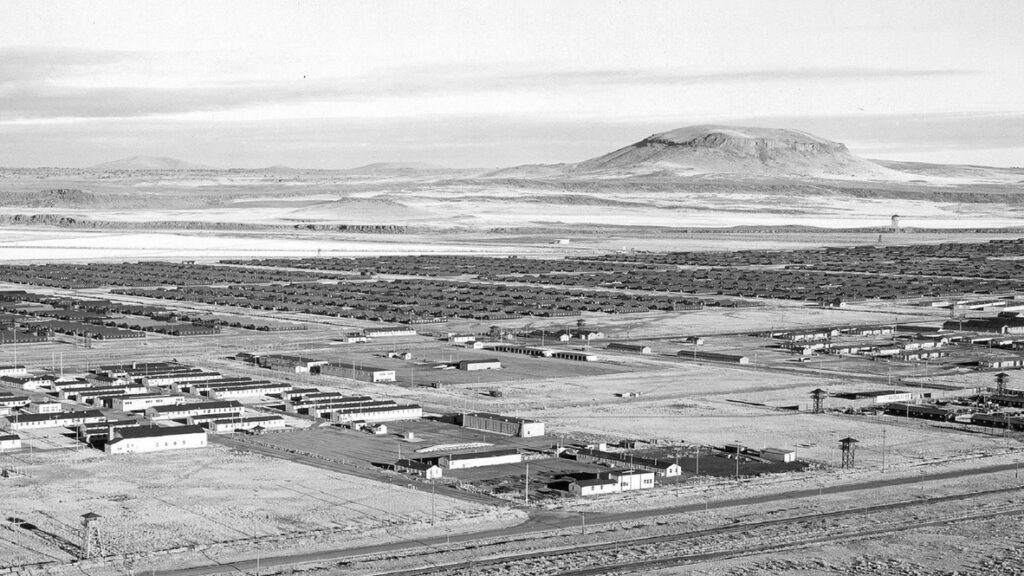

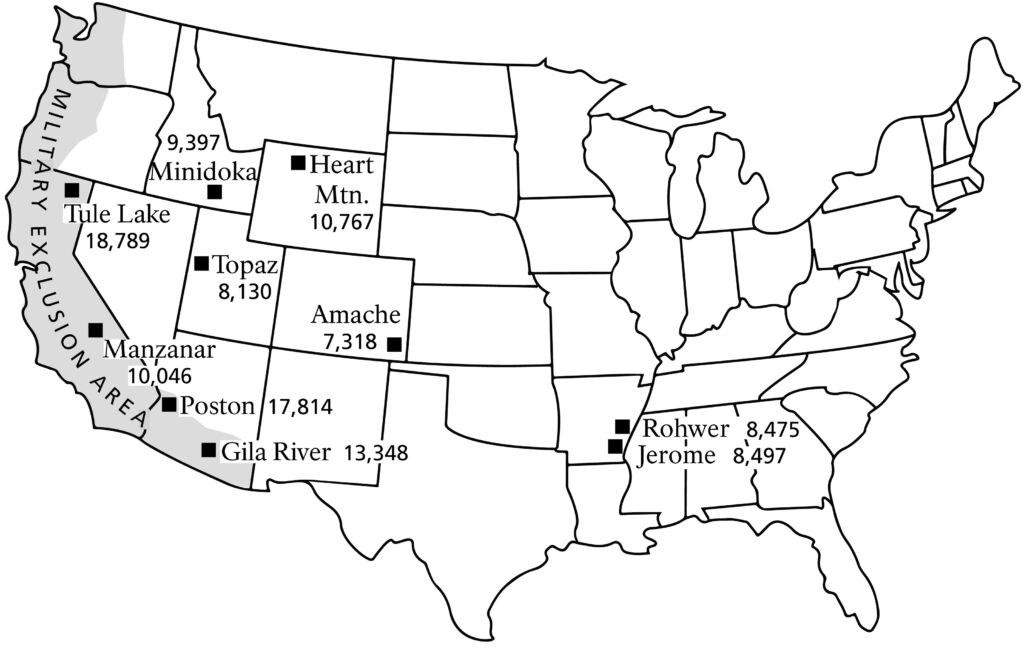

In the early months of 1942, following America’s entry into World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the U.S. Army to remove nearly 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry from their homes and communities on the West Coast; 80,000 of whom were American citizens. Tule Lake was one of ten remote War Relocation Centers to which they were sent. Enclosed barbed wire, the 7,400 acre center contained barracks, mess halls, and other buildings to house the 18,789 incarcerated Japanese-Americans, and 1,200 military and civilian staff who lived there between May of 1942 and March of 1946.

A Presidential Proclamation in December 2008 created the Tule Lake Unit within the World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument. However, on March 12, 2019, the Unit was separated out as its own national monument, thus becoming a separate item on my “Life List of National Parks.” As the site is only a seven minute drive away from nearby Lava Beds NM’s Petroglyph Point, I may have passed by years ago when I was checking that park off my list. None the less, this spring things fell in place for a return to northern California and visit my park #427. The New England National Scenic Trail should become #428 in the early Fall, leaving only Hawai’i’s Honouliuli National Historic Site to be visited (I think this will be my sixth continually expanding list completion). However, as the HONO site remains closed to the public for the foreseeable future, completing my List once again anytime soon is problematic. Maybe I can arrange a gig as a “Volunteer in the Park” at Honouliuli, if my hematologist will allow me that much time off???

Considering the original size of the Tule Lake camp, the park today is quite small. Factoring in the government’s thorough dismantling of the camp at the end of the world war, it’s amazing there are any surviving resources at all. Barrack buildings were cut in half and given or sold to new homesteaders in the Tule Lake Basin: Any time you see the distinctive nine-pane window in the area, it probably marks a structure whose origin was at the camp. Steel from the jail facility within the stockage was removed and sold as scrap. Fortunately the purchaser of these original jail cells and doors realized their long term historic significance and stored them for a half century, so they were available for donation back to the Park Service when restoration of the old jail began.

Today, the Ranger tours that provide access to the site do a great job explaining what is arguably the most complex story of the four such relocation camps currently preserved and interpreted by the NPS. At the heart is the impact of two poorly worded questions (# 27 & 28) from a loyalty questionnaire distributed in 1943. In 1988, the U.S. government formally apologized to each individual incarcerated during World War II, after determining such actions were the result of “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.”

Four of these ten sites are operated as part of the National Park System:

Amache, Manzanar, Minidoka, and Tule Lake

Fallen Leaf

Worn down by Washington politics, a discouraged National Park Service Director Stephen Mather travels to the Lake Tahoe area in July of 1919, to rest and perhaps recharge his batteries. On checking into William W. Price’s Fallen Leaf Lodge, Mather learns he is over an hour too soon for dinner. The desk clerk suggests an early evening stroll along the lake.

A short ways down the shore, Mather observes a small building packed to overflowing. His curiosity piqued, Mather joins the excess crowd standing outside, listening through the open windows to an informal program featuring owl calls by Professor Loye Holmes Miller. Enthralled by Miller’s skilled mimicry presenting bird notes his fellow campers might hear, the audience sits in rapt attention.

Although Mather is unable to connect with Miller that evening, he immediately envisions how popular such a Nature Guide activity might be in the national parks. Following up on this notion, Mather connects with Dr. Miller a few days later, proposing Miller come down to Yosemite and begin such a program immediately, right then and there! Citing a need for preparation, but impressed with the director’s enthusiasm, Miller agrees to start in Yosemite the following summer. And the rest, as they say, is history.

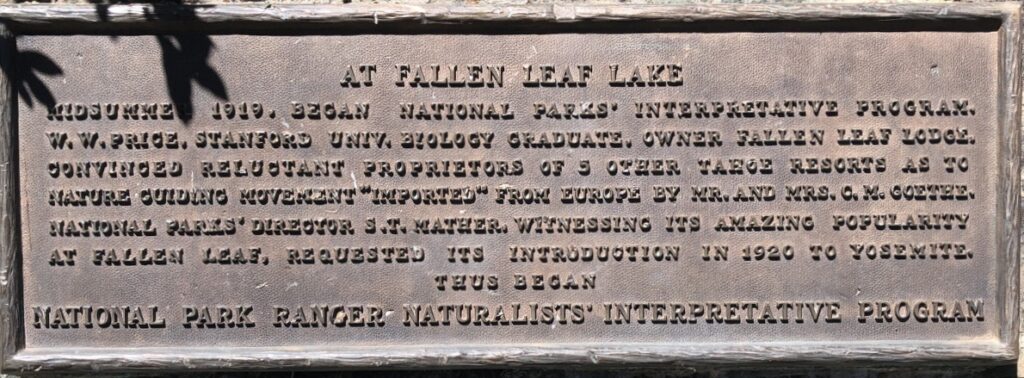

In later years, Dr. C.M. Goethe had a plaque placed at the spot. [Prior to World War I, Mr. & Mrs. Goethe had become interested in nature education in Europe (specifically the Swiss Nature Guide Movement) and had encouraged similar programs in the United States]:

AT FALLEN LEAF LAKE

Midsummer 1919, began National Parks’ Interpretive Program.

W.W. Price, Stanford University biology graduate, owner of Fallen Leaf Lodge, convinced reluctant proprietors of five other Tahoe resorts as to Nature Guiding Movement “imported “ from Europe by Mr. and Mrs. C.M. Goethe.

National Parks’ Director Stephen T. Mather, witnessing its amazing popularity at Fallen Leaf, requested its introduction in 1920 to Yosemite.

Thus began National Park Ranger Naturalists’ Interpretive Program

Now 105 years after the event, and while in the area working for the sixth time to re-complete my “Life List of National Parks” (currently I’m at 427 parks visited of the 429), I decided it was well past time to visit this plaque.

I learn the old Fallen Leaf Lodge has evolved into the Stanford University Alumni’s very successful Stanford Sierra Camp. Morgan Marshall of their staff responds to my inquiry: “In my 21 years of living/working here at Stanford Sierra Camp and Fallen Leaf Lake, you are the very first person to reach out and ask about the plaque. We point it out to our visitors, but it is oft overlooked. Rest assured, though… it DOES still exist!” On June 12th, Morgan was a very gracious host while we toured his wonderful facility.

This trip began as a bucket list item, but it became a pilgrimage: For NPS interpreters, this is indeed Holy Ground…

Loye Holmes Miller: The Interpretive Naturalist

Raymond B. Cowles, Willa K. Baum, Lois Chambers Stone, Leonard R. Askham, G. Davidson Woodard, John B. Cowan and Loye Holmes Miller

ORGANIZING THE FIRST NATURE GUIDE SERVICES

INTERVIEWER: LEONARD R. ASKHAM

ASKHAM : The following is a personal interview with Dr. Loye H. Miller, Professor Emeritus of Zoology, University of California at Davis. Dr. Miller is 95 years old and continues working even in retirement by holding office hours at Davis from eight to eleven each morning. His afternoons are spent relaxing and writing. Several papers are now in the process of being published. The interview was conducted at Dr. Millers’ home in Davis on 17 October 1969. My name is Leonard R. Askham. I am a graduate student working toward a Ph.D in forestry at the University of California at Berkeley.

MILLER : Very good, Mr. Askham. Start shooting.

ASKHAM: Thank you. We started this idea of interviewing again with a letter from Herb Evison. He was stating that you and Dr. Bryant were instrumental in starting this nature study program. Would you tell us how it came about and how you started it?

MILLER: The nature study program in the national parks was started by Bryant and myself. It came about by Steve Mathers ’ hearing me talk to some fellow campers at Fallen Leaf Lake in the Tahoe region.

FALLEN LEAF LAKE

MILLER: I went to Fallen Leaf Lake in 1919 to spend a vacation, a summer vacation. I camped there at the lodge, or in the neighborhood of the lodge, which was kept by an old schoolmate of mine when I was a boy, and later a colleague in field work, Billy Price (in other words, W. W. Price). I went there to get rested from a very strenuous year at Los Angeles. He had a way of asking the fellow campers to meet every Sunday in a little building, an auditorium, and also on Wednesday evenings they would get together there, all just for fun. Someone of the group would supply a few remarks or talk or a song. I was one of these people among several. One was a sea captain. One was a fisherman. One was a forester. Your former chief for whom your building is named was there one evening.

ASKHAM: Walter Mulford?

MILLER: Mulford, yes. It so happened that one evening I was talking about the bird notes that people around there might hear. I had developed some measure of skill in mimicry, and I talked about the various calls of owls. I am told later by Stephen T. Mather that he was passing by the open window to go over and register at the lodge. He saw people, not only in the assembly hall but standing and watching through the windows, listening to this talk. And I am told that there he got the notion of just such activity in the national parks. Well, he went on. I didn’t meet him. I didn’t know he was out there in the dark listening. He went on over to Tahoe.

BEGINNINGS OF YOSEMITE PARK TOURS

MILLER: I got back from one of my walks up in the country back of the lodge, and here was a telephone message for me to call Mather at Altahoe, a station down on the big lake. I called him, and he wanted me to come over to Altahoe and talk to him and with him about this very subject. He proposed that I get in my little wagon-I drove a 1914 Ford, loaded with family (I had two boys and a wife)- and come right on down to Yosemite and start now, right then and there. Well, I didn’t feel as though I could for two reasons. I had already spent my summer, and I had to get back to Los Angeles and go to work again. Second, I didn’t want the thing to start off “like a rocket and come down like a stick,” with no previous preparations. So I got his agreement on this; he quite concurred that we should start it the following summer in Yosemite.

ASKHAM: Was Bryant working with you at the same time on this?

MILLER : Well, that’s another point which has never been corrected. I’ve tried and tried to get it properly recorded. I was there as a vacationer. Billy Price did nothing at that time, so far as I am aware, for the establishment of an interpretative biologist in his camp. So I, going around from day to day, was met by some of my fellow campers and was asked if they could go along with me on some of my walks. Well, I didn’t mind. I was learning a lot of interesting things, and they like the same sort of things. So one or two of them (I think they were from Long Beach) went on one or two of my walks. Some of the other folks found out about this, and they came to me with a proposition that I take them along. They would like to pay me a small fee for my services. Well, I demurred a bit but eventually we agreed. On three days a week-three mornings from about eight until ten or eleven-we took walks in the vicinity. They agreed to pay me fifty cents apiece or a dollar a week for the three days. I said, “All right. Come along.”

ASKHAM: That was pretty good money then, too, wasn’t it?

MILLER : In those days, that wasn’t bad money and I was there at considerable expense myself and on a small salary at home. First thing I knew, I had 15 or 20 followers. That was the work I was doing at Fallen Leaf Lake in the Tahoe region all that summer. Now it so happened that a man by the name of Goethe, of Sacramento, had influenced the State Fish and Game Commission of the State of California to send a man to ten different centers of summer vacationists around Lake Tahoe. He was to talk with them about the natural history of the region in which they were kept. He was paid by the State Fish and Game Commission assumedly, as near as I can learn. The plan was under the stimulus of Mr. Goethe.

ASKHAM: This was in 1914 also?

MILLER: No, this was in 1919.

ASKHAM: Mr. Stephen Mather came through and interviewed me on 21 July of that year, 1919. The following week, I think it was, Bryant and his family and Mr. Goethe and his wife in their circuit around the Lake Tahoe area came over to Fallen Leaf Lake. Bryant spent a week there as he had in other areas around Tahoe. Somehow or other the impression got out that Bryant and I were both employed by somebody, and I, assumedly, by my chum, Billy Price-which I was not. Now that is a mistake that has lived 50 years or more.

ASKHAM: Well, now it’s rectified.

MILLER: No, it isn’t corrected. It can’t be because this very good friend of mine, Mr. Goethe, now passed on, had a bronze tablet cast and mounted on a big pine stump and placed on the former grounds of Billy Prices ’ station. That plaque still stands there with this statement on it. Unless you take a chisel and cut it off, it’s there to stay.

ASKHAM: What was the statement?

MILLER: The statement was that Bryant and Loye Miller were doing the same thing, or that when he came there, he found Loye Miller doing this same work for Mr. Price, which is not the case.

ASKHAM: You were on your own.

MILLER: Yes. Furthermore, he has his own name on there: C. M. Goethe. He later had cast in bronze another plaque which is mounted upon a great granite boulder set up at Yosemite. In this he states that here under the beautiful walls of this Yosemite, Stephen T. Mather got the inspiration for the nature guide service, which is not the truth.

ASKHAM: He got it at Fallen Leaf Lake in Tahoe.

MILLER: Yes. And unless you take a chisel and hammer and cut that bronze tablet all to pieces, it still stands there. So you say that it is now corrected-it is not now corrected. I have written to various people stating my relation. I get very nice letters and yet again and again, there come out statements that Loye Miller and Harold Bryant were doing this work at Fallen Leaf Lake in Tahoe.

ASKHAM : To continue, you said that you wanted some time to think about your program before you started it when you talked to Mather. What did you do this next winter?

MILLER: The next winter I went back to my job in Los Angeles, and I didn’t have time to think about anything else. I did promise Mather that I would come. Unfortunately, the little leaflet that is handed out to visitors when they enter the park did not carry any announcement of this service. That’s what I had expected Mather to take care of. It slipped up somewhere. We know not where.

ASKHAM: This is 1920 now?

MILLER: Yes, that was 1920. So I arrived in Yosemite with my family and my little tin wagon to camp on the shores of the river there, the Merced. I found that Bryant had already arrived. I had to teach at Los Angeles until a later date so I did not arrive until late June 1920. Bryant had arrived a week or two earlier. He had set up a very nice schedule of work. I examined that schedule and wholeheartedly agreed with his plan. Every day we wrote up for the chief of the park, the superintendent, a statement of our activities together. I endorsed with Bryant this statement each morning, just as a captain reports his activity to his colonel. Those reports presumably are on file somewhere in the archives of Yosemite.

Sarcodes sanguinea

Tuesday morning, Lassen Volcanic National Park posted the accompanying photo with this description: “One of the first signs of life after a long winter is Sarcodes sanguinea, also known as snow plant. Snow plant can be found growing near conifers, striking and dramatic against the melting snow. Even though plant is in the name, snow plant has no chlorophyll and does not need the sun to survive. Instead, it gets all the nutrients it needs from fungi in the soil. Snow plant depends on the community around it to survive and thrive.”

We were so fascinated we hopped on the next plane to Reno, to see if we could see one in person. Although we were never able to find one just sprouting from the earth with that classic pineapple shape (initially the plant has long fingerlike twisting scales wrapping the plant), we were rewarded with our first sighting (a more mature plant with delicate urn-shaped blossoms), complete with identifying sign!, at the Tallac Historic Site on the south shore of Lake Tahoe [a century ago the “Grandest resort in the World”!], and then with even greater success on Lassen’s Lily Pond Trail at the park’s northwest entrance. We obviously timed our trip perfectly for this beauty’s growing season!

Sarcodes sanguinea is rare and protected by law. Our waitress in Mineral CA, said, anyway, they are poisonous (paraphrasing “leaves of three” with “red means dead”), but according to botanist James L. Reveal (via Wikipedia) S. sanguinea is edible, if cooked. The root is said to have a texture and flavor similar to asparagus.

Due to its unique and striking appearance, coupled with its relatively limited geographic distribution (CA/OR/NV), S. sanguinea has been a popular subject of various California naturalists. In his 1912 book, The Yosemite, John Muir wrote this description of Sarcodes:

“The snow plant (Sarcodes sanguinea) is more admired by tourists than any other in California. It is red, fleshy, and watery and looks like a gigantic asparagus shoot. Soon after the snow is off the ground, it rises through the dead needles and humus in the pine and fir woods like a bright glowing pillar of fire… It is said to grow up through the snow; on the contrary, it always waits until the ground is warm, though with other early flowers it is occasionally buried or half-buried for a day or two by spring storms… Nevertheless, it is a singularly cold and unsympathetic plant. Everybody admires it as a wonderful curiosity, but nobody loves it as lilies, violets, roses, daisies are loved. Without fragrance, it stands beneath the pines and firs lonely and silent, as if unacquainted with any other plant in the world; never moving in the wildest storms; rigid as if lifeless, though covered with beautiful rosy flowers.”

Lava Beds National Monument, California

After completing our visit to Tule Lake NM, we drove through nearby Lava Beds National Monument on our way to Burney CA. We stopped at two above-ground features I had bypassed on my previous trip to Lava Beds: Petroglyphs Point and Captain Jacks Stronghold.

For thousands of years, hills northeast of the present Lava Beds caves were an island. Ancient Lake Modoc lapped against its base, scouring cliffs. Later, Native Americans canoed to these cliffs to carve symbols in the soft volcanic tuff. The meaning of these symbols remains a mystery, but Modocs still tell of Kanookumpts, creator of the world, who sleeps here.

At the stronghold, half-mile and mile-and-a-half loop trails allow exploration of an area on the old lakeshore where Modoc families took refuge as they fought for their homeland.

Petroglyph Point

One day Kamookumpts was resting on the east shoe of Tule Lake. Looking around, he realized there was nothing anywhere except the lake. He decided to make land. He dug some mud from the lake bottom and made a hill, then land and mountains. He also created rivers, streams, plants, and animals. As the mud dried, the hill became rock, still visible today.

Captain Jacks Stronghold.

Kintpuash, also known as Captain Jack (c. 1837 – October 3, 1873), was a chief of the Modoc tribe of California and Oregon. Kintpuash’s name in the Modoc language meant ‘Strikes the water brashly.’

Walking through the trenches of the Stronghold reminds of the courage it took for a small band of Modoc people to endure the winter of 1872-1873 here. It took the Army five months to drive the Modoc from the Stronghold, and soon after from their entire homeland. Still, a modern culture of Modoc descendants survives, especially in Oregon and Oklahoma. You may see prayer ribbons and sage offerings hanging on the medicine pole near the junction of the two trails, signifying the continuing importance of this special place.

Burney Mountain

Our plan, five months in the making, was to drive the road through Lassen Volcanic National Park and stop to hike Lassen Peak along the way. Unfortunately, the park’s work removing the winter’s accumulation of snow had drug on since March and was not completed before our arrival. We needed a last minute alternative, which we found looming over us when we woke up in little Burney CA: the 7,863 foot Burney Mountain, a lava dome complex and small stratovolcano located about five and a half miles south-southeast of town. Burney Mountain last erupted about 230,000 years ago, but much more recently, the eastern side of the mountain was burned in the 2014 Eiler Fire.

For our purposes, Burney Mountain was appealing because there was a road to the summit and a fire lookout tower, still in use today, which we could see as a small dot from town.

The approach dirt road was lengthy, but in good condition, if you had high clearance. The final five miles (Forest Service 334N23) featured sixteen switchbacks and that section alone took us an hour to drive. We parked and hiked the last kilometer to the tower. The fire spotter on duty makes the drive on a daily basis, and was just starting his 39th season.

Although conditions were a little hazy, the summit offered an awesome 360-degree view of Mount Shasta to the north and Lassen Peak to the south, as well as other nearby peaks such as Crater Peak (slightly taller at 8,677’), Black Butte, Castle Crags, and Soldier Mountain.

Section Hike on the Pacific Crest Trail

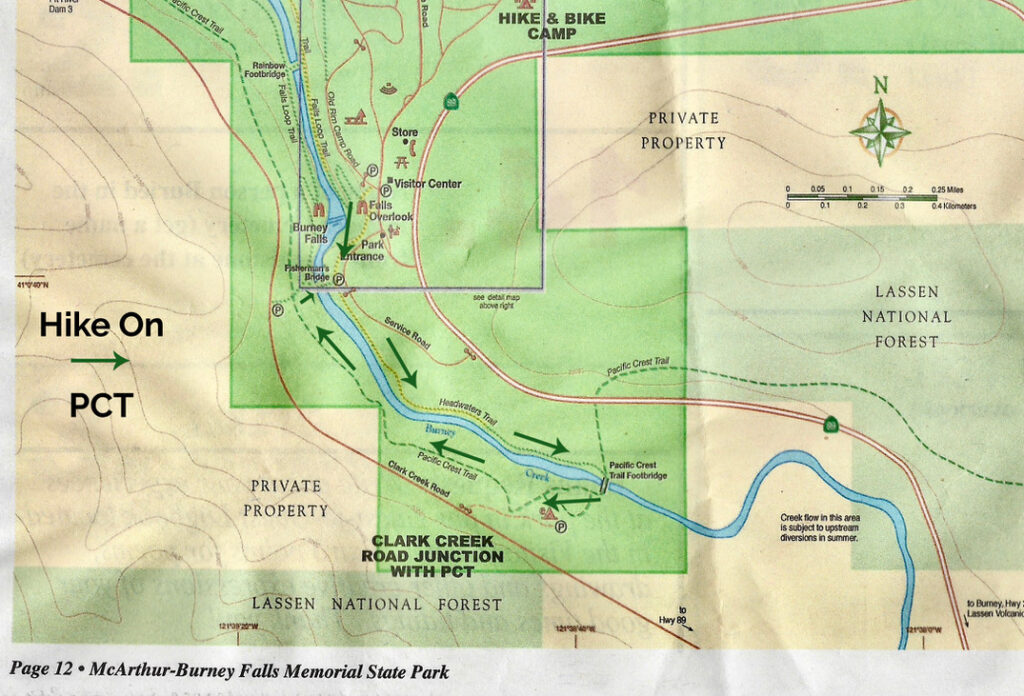

Beginning in 2013, we have done occasional hiking on the Pacific Crest Trail. As our drive from Tule Lake to Lassen brought us in the neighborhood, we decided it was time to add another section of the PCT to our resume. We found a safe parking area overlooking the scenic Burney Falls, and pulled out our hiking poles for a pleasant afternoon loop covering both side of Burney Creek, including a little over a mile on the PCT.

By our calculations, this brings our total Pacific Crest Trail mileage to 110. At this current average of ten miles per year, we feel confident in predicting completion of the entire PCT by 2269…

[And yes, for those keeping track at home, that means we parked in Burney SP, saw Burney Falls, hiked over Burney Creek, slept in Burney, and climbed Burney Mountain.]